Greenwich Council is canvassing our opinion as to the possible use of the Woolwich Barracks when they are redeveloped after the army (apart from the King’s Troop) moves out in 2028.

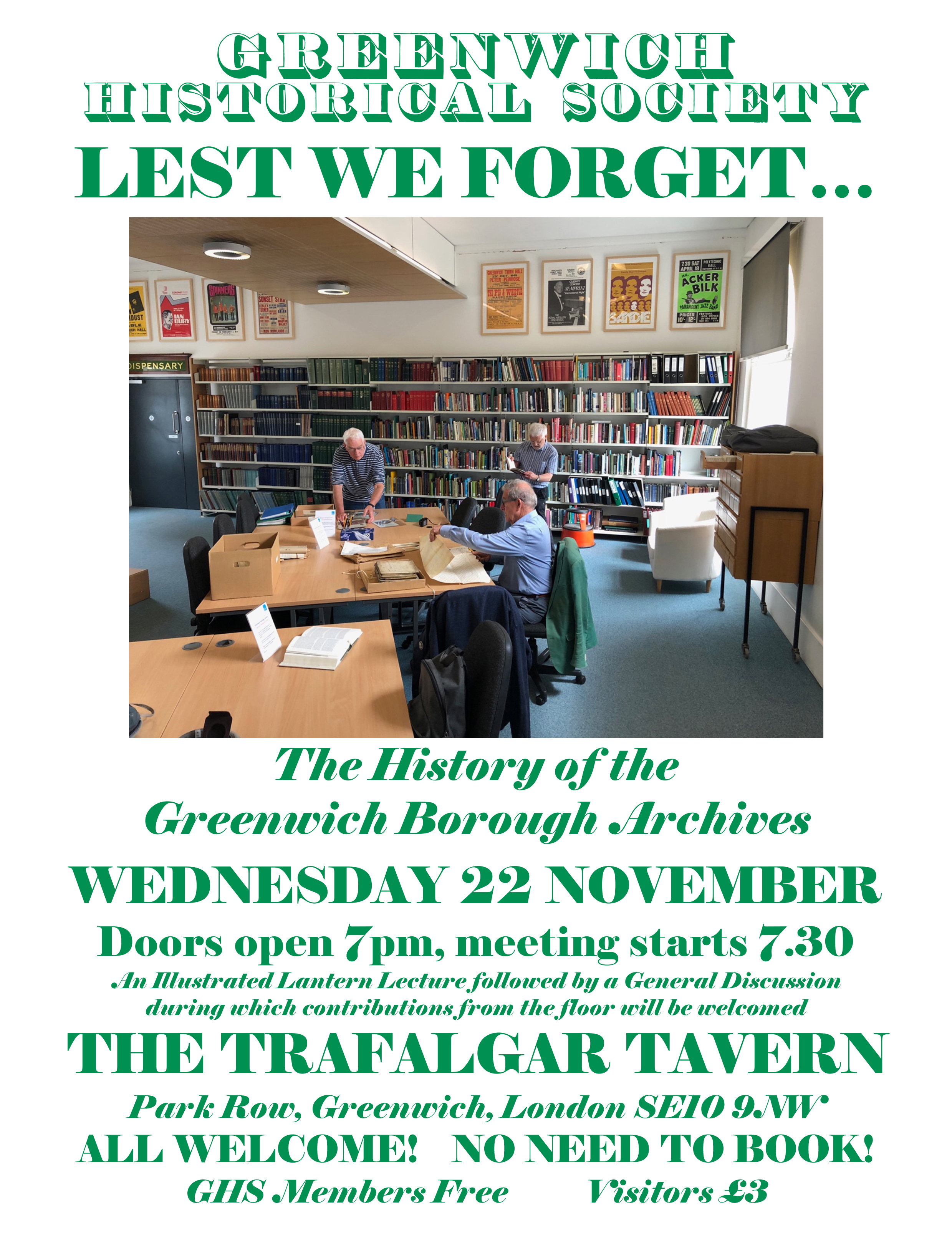

Surely a part of the site would make an excellent headquarters for the Borough’s Archive and Museum, rescuing it from its present obscurity at Anchorage Wharf. It is located in the heart of the Borough, spacious, relatively easily accessed and (despite what is claimed in the text) safe from flooding.

You may note in the blurb preceding the questionnaire, the following statement:

“Any proposed development or changes of use must make a positive contribution to the distinctive character and heritage of the site, and improve connectivity with the surrounding area.”

Let’s try to hold them to this. Please open document by clicking on the link below.

It doesn’t take very long to complete – maybe 10 minutes according to how much you may wish to elaborate basic statements. Please note however, all submissions must be made SOON. The closing date is MARCH 17th.

http://royalgreenwichplanning.commonplace.is/en-GB/proposals/woolwich-barracks-survey/step1