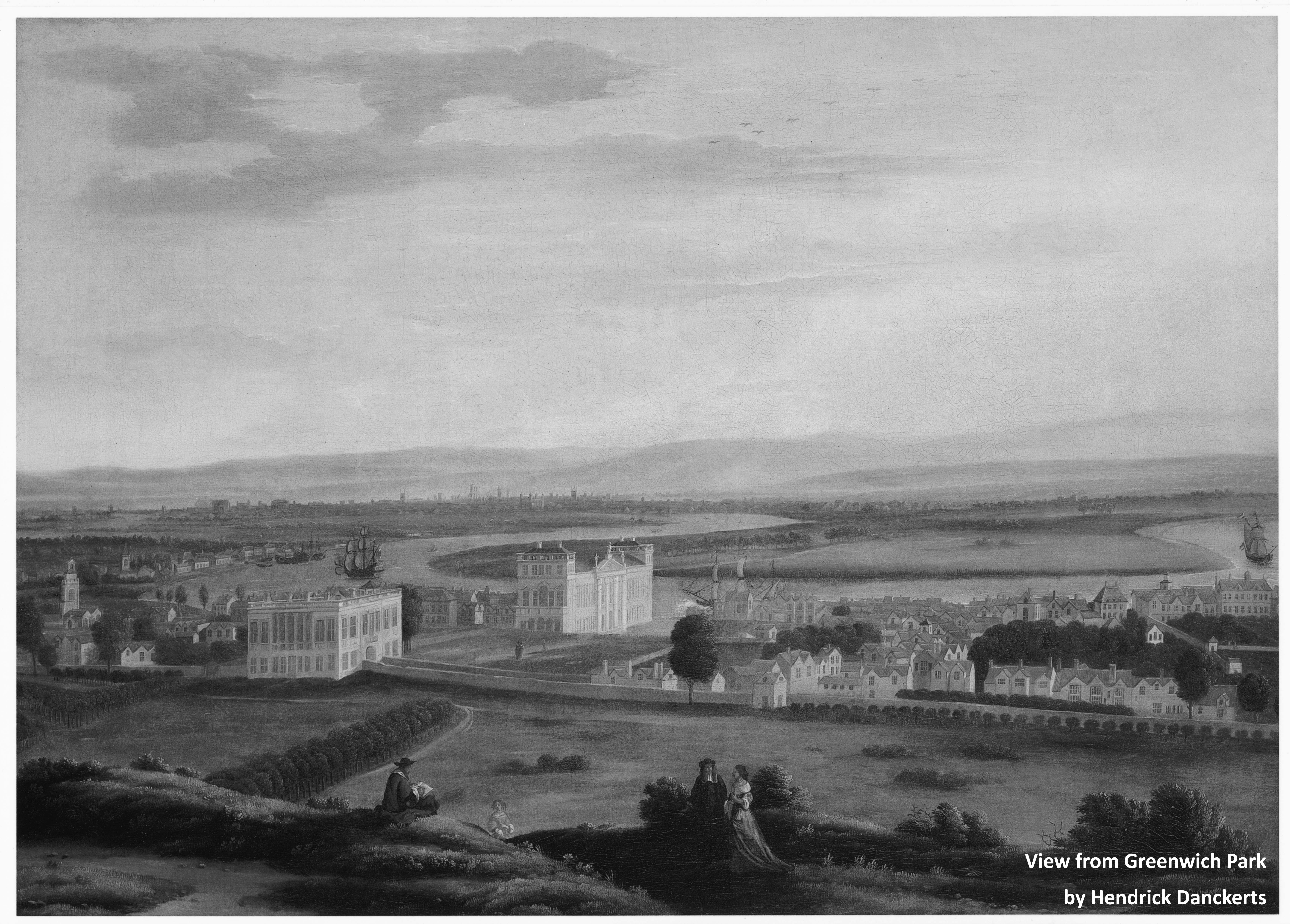

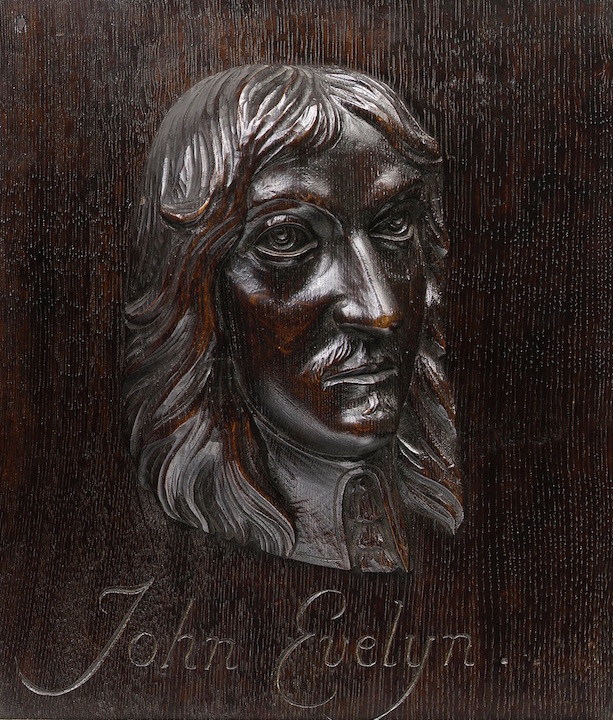

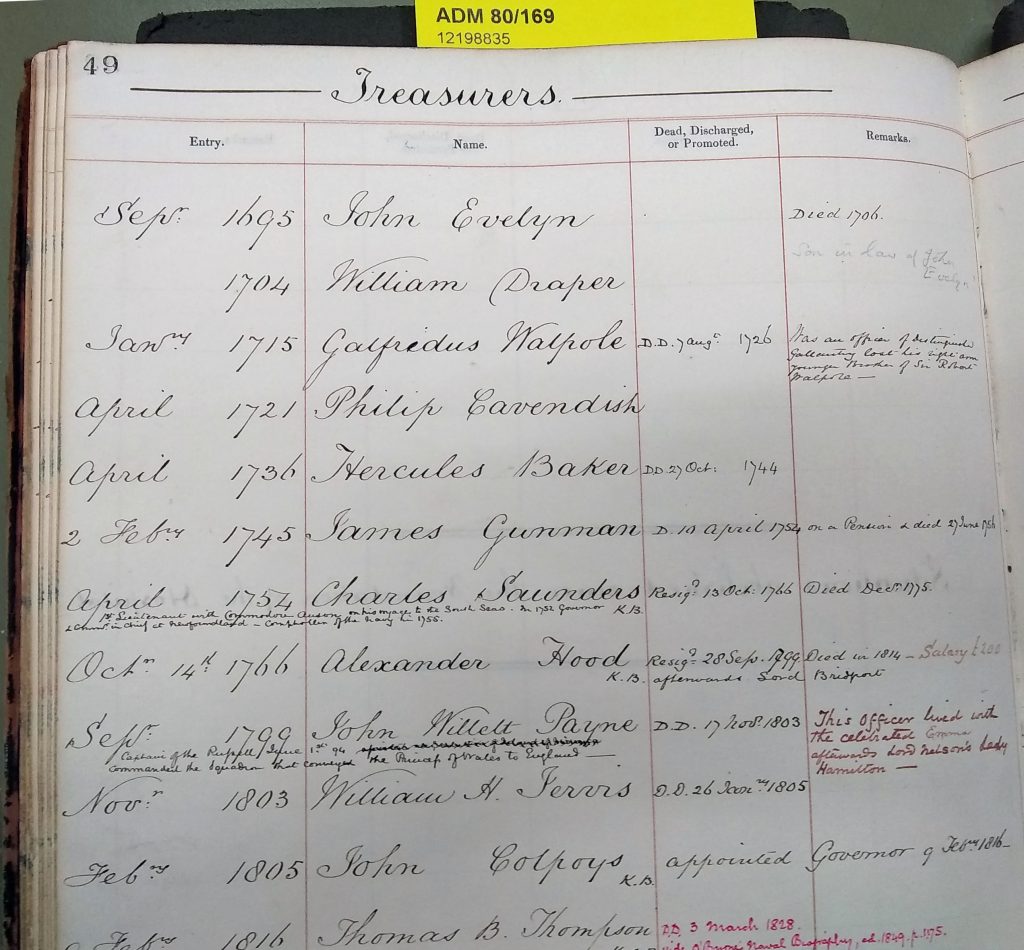

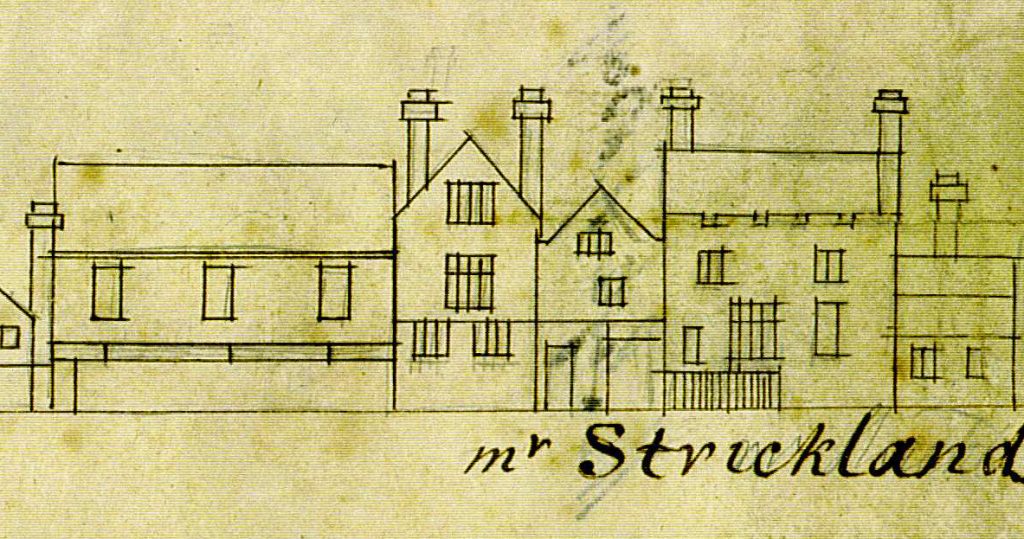

June Burkitt was Greenwich Council’s first Local History Librarian. She was appointed in 1961 and I had the privilege of working as her assistant. She encouraged me to become qualified and I was able to succeed her as Local History Librarian in 1969 when she left the council’s service. She remained a member of our society, serving as hon. secretary for ten years from 1963. She was a member of the society’s council and president for two years. ‘Greenwich at the End of the Seventeenth Century’ was one of her two fine presidential addresses. It is a thoroughly researched and well written account of Greenwich during a time of serious economic decline following the departure of the Stuarts from Greenwich Palace.