‘Greenwich Park or EASTER Monday’ is a print published by John Marshall & Co around about 1800 in which we see displayed all the fun of the fair at a time before the ‘chicks and chocs’ of the modern-day experience formed our vision of the occasion.

Here then is a picture of all and sundry, high and low, relaxing and recreating together. The rigours of winter were over, the denial of Lent and the solemnities of the Passion were done with, and it was time to roll away the stone.

Traditionally, two separate festivities were held in Greenwich each Spring, one at Easter, (whenever it fell), and the other at Whitsun. The Greenwich Fair depicted here and the one Dickens described in his ‘Sketches by Boz’ some thirty years later may seem the same, but are quintessentially different. By Dickens’ time a re-branding of the event had happened. The days of an archaic pre-industrial calendar festival were numbered.

In his essay, ‘Greenwich Fair’, (published in Transactions, Vol. VII, No4, 1970), Ronald Longhurst reminds us that, “the origin of [Greenwich] fair is rather obscure … and it seems unlikely that as a sizeable event it dated from earlier than the eighteenth century.” Greenwich Fair was never a chartered market for the buying and selling of produce, livestock and the hiring of labour. Its original intent was solely to provide amusements. The earliest reference dates from 1709.

Celebrations opened on Easter Monday. Visitors would arrive in Greenwich, either up from the country, or down from town; either way they were bent on pleasure and recreation. (Think of it as a bit like a few days at Glastonbury or Reading).

Those coming from the Metropolis would be best to have travelled by water as coming by land would have presented them with particular difficulties. They might have got into the town via Deptford Bridge and from thence along the London Road (nowadays Greenwich High Road). Until the early 1800s there was no bridge across the Ravensbourne on Creek Road (as we know it today) to carry them over. Those up from Kent would probably have come in over Blackheath or by Woolwich. Any road up, they would have been greeted by stalls offering an assortment of sweet-meats, trinkets, tricks and treats. They would make their way through town because as Greenwich Park was the ‘fairground’. Before 1830, the park was essentially a private space and only opened to the general public on special occasions like these. It beckoned them with fresh air and space and so offered – in good weather at least – the opportunities to sport, picnic and gambol and dance. In short, to turn the world upside down.

Much of what can be seen in the image is described in this cutting from The Star (London) of Tuesday 20 April 1802. Referring to the previous day, it reported that:

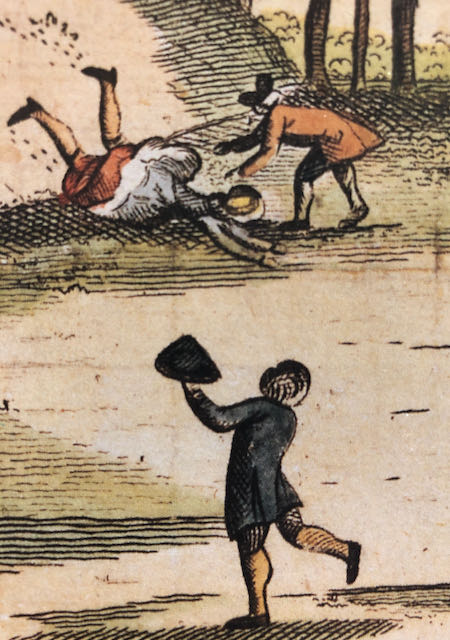

“GREENWICH HILL was … thronged with its annual visitants, and the delightful walks in the Park covered with gay fantastic groupes of Holiday-folks, resolved to be merry, displayed a scene pleasing, animated, and picturesque. Care, frightened by the voice of Cheerfulness, fled the spot, Pleasure sparkled in each eye, double reflection stood suspended, and nought was heard but playful repartee, roguish tittering from the cherry – cheeked damsels, and hearty peals of laughter from their hail admirers. The fineness of the weather tempted numbers of adventurous Fair to a tumble down the hill, persuaded no doubt that in the eyes of their Adonis, a ‘green gown’ would prove the most inviting attraction, and determined, from a principle of national pride, to afford convincing proof that British Females possess a perfection of shape and symmetry of limb rivalling, if not surpassing, the boasted beauties of Greece or Rome. Various sports succeeded, to the approach of evening forbidding the continuance of Rude Amusements, the jocund party separated to conclude their pleasurable day, as Fancy might dictate.”

‘Green gowns’? ‘Tumbling’? Shall we join the dance?

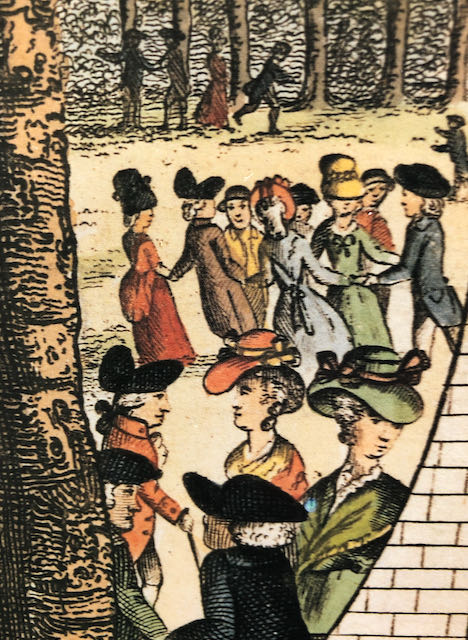

This is ‘Kiss-in-the-Ring’ – a game involving elaborate manoeuvres, but which eventually, after lots of ins and outs, twists and turns, had its own reward …

… over to the left, (though apparently of little interest to the courting couples in the foreground) is a boxing-ring where a bare-fist fight is taking place …

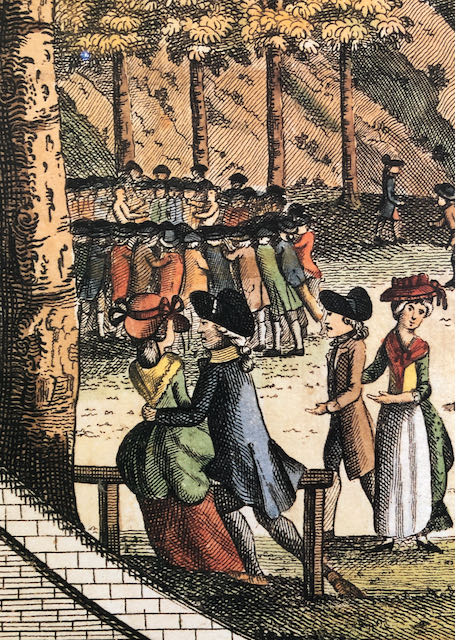

… This sailor-boy and his lass engage at close quarters of their own, whilst just to their right, a respectable couple saunter by rather aloof to it all: good luck to them! On 7 April 1763, The Derby Mercury reported that: “On Monday last a gentleman and his spouse walking in Greenwich Park, the rabble catched hold of her leg, dragged her down the hill, and tore almost all the cloathes off her back, during the transaction she lost her shoes and silver buckles, and continues so ill of the fright that her life is despaired of”…

Aha! There’s some refreshment to be had. Very likely, after the long trek visitors would be ready for a drink, (and no doubt the longer the day wore on, the stronger it got). Most sources mention a penchant for gin, and a nip of ‘ruin’ is probably what this lady is doling out here to the Greenwich Pensioner and his friend from Chelsea. Behind her a cheeky chap gets his by more nefarious means. And, oh, whose is that badly brought up little dog? For goodness sake. Decorum, please!

But it’s up on the Hill itself where the real action is at. The great ‘sport’ on these occasions was for the young blades to coax the girls up the hill and then to run, roll and tumble down together. ‘Tumble’ is a word to look up in Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. There you will find its other definition, but perhaps you guessed its connotation already …

… the participants landed in a dishevelled heap at the bottom! And very likely it was a spectator sport too, what with the a glimpse of an ankle, perhaps an uncovered calf, even a bare bum.

Such pleasures and pastimes conjure up a golden age full of innocent fun. However, scratching and sniffing the image with the nose of a modern sensibility gives rise to suspicion and the rosy scent soon wears away. But don’t entirely let go of this lovely illusion. This picture still evokes a particular moment which may perhaps have marked the heyday of Greenwich Fair.

Shortly after this print was published something changed. And it was a visible shift. In 1814 the Hospital Commissioners granted the piece of land between the park wall and Romney Road for use by the fair . It was an attractive proposition to the travelling showmen Richardson, Wombwell, et al., who soon moved in and rapidly spread through the town as far as Deptford Creek, establishing what one Mission pamphlet in 1837 described as “the greatest Carnival this side of the bottomless pit”.

The steamboat companies, and after 1840, the new railway, multiplied the number of visitors, bringing in far more than the town could cope with. Nor were they quite the same folks who had frolicked about in Marshall’s quaint depiction. These were a new kind of working people, wage slaves working in factories, some of whom used the occasion, not just as a recreation, but as a release from the sordid conditions they endured. Their intent on enjoyment was fuelled by alcohol if the newspapers and other accounts are to be believed.

Complaints began almost immediately. Then, in 1825, St Mary’s was established as a ‘chapel of ease’ to St Alfege church just below the park gates at the top of King William Walk. Perhaps this acted as a catalyst to the groundswell of opinion: It was inappropriate to have these anarchic revelries going on to the detriment of the peace and morality of the town.

The gist of this opinion was expressed in this quotation from the petition delivered to the Justices of the Peace by the Vicar of St Alfege, his Churchwardens and Overseers, Governors and Directors of the Poor in April 1825:

“That of late years … the whole scene has been materially changed, that the profligate numbers of the lower orders have been increased, that the money heretofore spent in the Town, and to the benefit of the Tradesmen generally, is now almost entirely squandered in the numerous Booths and Shows … and that a very great addition is made to this evil by the increased – the open and powerful – incentives to licentiousness among the middle and lower orders of the community, that the hours kept by these booths are in direct violation of the laws of the land, and the scenes to which they lead are offending against the best feelings of Christian morality”.

The showmen were given notice to quit, but even then they were an a most unconscionable time packing up their tents and booths. It did not finally close until 1857.

Poor old Greenwich Fair: gone, but not forgotten – and as Punch quipped sardonically, “… Not a bit lamented, pickpockets and gents alone excepted”.

Happy Easter Monday!